OPERATION LONGSHANKS

David Miller

The British raid on the German merchant ship Ehrenfels in Goa in 1943 remained a closely guarded secret until the publication of the book “Boarding Party" in 1978, which was followed in 1980 by the film “Sea Wolves". Both book and film were based on the genuine story but with many added fanciful elements, some for dramatic effect, or in the case of the film, to satisfy the egos of certain actors. Both also gave the impression that the raid was mounted by a handful of middle-aged accountants and tea planters, using an antiquated, steam-propelled barge as transport. There is a grain of truth in all of that, but the reality is that it was a warlike operation with a serious aim, carried out with precision and which resulted in five deaths, the total destruction of four merchant ships and their cargo and, most important of all, the total elimination of a major threat to the Allied naval operations in the Indian Ocean.

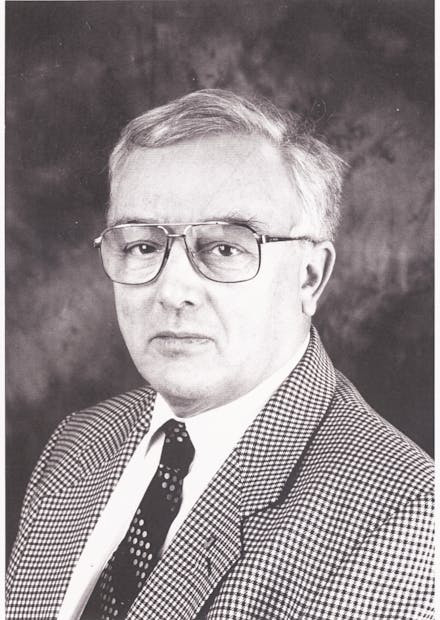

1 - German merchant ship Ehrenfels.

Portugal was neutral in the conflict, a very difficult role to play. At home the Portuguese found themselves unwilling hosts to the intelligence organisations of both sides. Further, in 1942 Portugal acted as the intermediary between the Allies and Japan for two major exchanges of diplomats and civilian internees, both at Lourenço Marques. The first took place on 28-29 July 1942, involving the US-chartered Swedish liner, Gripsholm, on one side and the Japanese-owned Asama Maru and Japanese-chartered Italian liner, Conte Verde, on the other. A similar British-Japanese exchange took place, also at Lourenço Marques. between 27 August and 16 September 1942, involving four British liners and two Japanese. All ships sailed under “safe passage rules" and completed their voyages unharmed.

Portuguese Goa was a small enclave some 3,700km2 in area and in 1940 had a population of just over 5million. It had been a Portuguese possession since the Sixteenth Century and was headed in 1940 by the Governor-General, Colonel José Ricardo Pereira Cabral (1879-1956). He knew the British well, having been appointed Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1919 and Knight of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1940, most unusual honours, which may have made him well-disposed towards the UK. British India was represented in Goa by a Consul, Lieutenant-Colonel (retired) Claude Bremner (1891-1965).

2 - Governor-General, Colonel José Ricardo Pereira Cabral (1879-1956).

By early 1943 the position of Goa was delicate. The colony was a long way from the Portuguese homeland and relations with the British were, of necessity, correct although at a personal level, cordial. But, as in the home country, the administration turned a blind-eye to discrete espionage on both sides. There was, however, a complication; the four Axis merchant ships in Marmugão Harbour which appeared fated to remain there until the war's end, although there was always the possibility that one or more might try to escape.

Legally, these ships were taking shelter, while their crews were visitors, not internees, which meant that as long as the ships lay at anchor, paid harbour dues and chandlers' bills, and their crews behaved with discretion, they were left to their own devices. The crews were allowed ashore and some even had small sailing boats which they used for fishing within Goa's territorial waters.

Germany rebuilt her merchant fleet after World War One and by 1939 had a substantial number of ships at sea, the great majority less than twenty years old. Inevitably, many of these were in foreign waters when war was declared on 3 September 1939, some of them on the high seas but many in port - there were no fewer than thirty-nine in the Spanish port of Vigo, for example.

All German ships' masters carried secret orders to be opened on receipt of codeword “Essberger", which was issued on 25 August 1939. This directed them to leave potentially hostile ports as soon as possible, or, if at sea, to leave the usual shipping lanes. Shortly afterwards a second codeword was broadcast ordering masters to head for either Germany or a neutral port. Some, which were in British or French ports were interned, some were able to reach Germany, but most headed for the nearest neutral port in order to avoid capture or sinking.

Having reached a neutral port, the German captains were faced with major problems. First, they had to maintain their ships and ensure that engines and other systems remained in working order and supplied with fuel and lubricants. Secondly, they had to look after their crew, making sure that they were fed, paid, given medical treatment and kept occupied. Thirdly, they had to make two sets of plans, the most important being for an escape, while the second was for destruction of the ship, either in port or on the high seas, if threatened with overwhelming enemy force.

Threat to Allies

The Axis ships posed military threats to the Allies since, if they escaped, they could be employed as Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMCs) or as supply ships to replenish both surface ships and U-boats. The British were also paranoid about the German ships being used to gather intelligence about ship movements, particularly sailings, which could then be sent by ship's radio to patrolling U-boats. The worst case for the Allies was that, despite all their precautions, the German ships would sail immediately after nightfall and then have many hours start until their absence was noticed the following dawn, by which time they would have disappeared over the horizon.

Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) submarines posed a significant threat to Allied shipping in the Indian Ocean. This was partly due to a shortage of escort vessels, anti-submarine aircraft and modern aids, although some of their success was because Allied merchant shipping sailed almost always without escort. There was, however, an even more ominous development - the Germans were coming.

The German Navy's main effort was in the Battle of the Atlantic, but it also sent boats southwards with considerable success, Gruppe Eisbär (Polar Bear Group) (four Type VIIC attack boats and one Type XIV tanker), sank twenty-four ships (163,100grt) around southern Africa during October 1942. Even before Eisbär had reached the Cape Dönitz sent another group, this time new long-range Type IXD2, which rounded the Cape and worked their way North to the Mozambique Channel, where they sank thirty-six Allied merchantmen between November 1942 and March 1943. Every one of the targets was sailing alone – easy pickings. These sinkings caused increasing alarm in various Allied headquarters and major efforts were made to find a cause. One possibility seemed to be that Axis submarines were being informed of Allied shipping movements and a rumour soon gained ground that there was a powerful transmitter aboard the Ehrenfels, which was transmitting nightly to submarines at sea. It was further believed that information on sailings from Bombay was being taken by courier to Goa, where it was handed to Robert Koch, a German resident, who then took it to Ehrenfels.

Codenames

It is necessary to clarify the codenames:

- Hotspur. Used within India for the kidnapping of Robert Koch on 17-19 Dec 1942.

- Longshanks. Allocated by London for raid on Goa and used by London and SOE(India) when communicating with each other.

- Creek. Despite the use of Longshanks, within India the actual operation was always referred to as Creek, but this name was never used when communicating with London.

Goan Garrison

The Portuguese permanent garrison comprised one company each of light infantry, mortars and artillery – about 500 men in all. There was no coastal defence, nor was there any anti-aircraft defence. By chance, a reinforcement battalion sailing from Lourenço Marques to Timor had been diverted to Goa, arriving in early February 1942. A small warship called from time-to-time and there was no air force. In total, the Portuguese garrison comprised two small battalions, with limited artillery support, which could have been brushed aside in a major British invasion, although they could be expected to provide resistance to small-scale raiding parties.

The Ships

Braunfels, Drachenfels and the Italian Anfora were not involved in the main action which follows, so can be quickly dismissed; all three were elderly and slow – in fact, typical 1920s tramps. But Ehrenfels was in a different category, being not only newer but also considerably faster and more capable. She had twin diesels driving a single propeller, giving long endurance on one engine and high speed on two. Such power also required the hull to be of significantly stronger construction than in a conventional merchant ship. She also had built-in bases for gun mounts and collapsible bulwarks which would hide the guns until required. By late 1942 the British knew that if Ehrenfels escaped she would undoubtedly make for Singapore where she would be outfitted with guns and ammunition from Japanese or captured British stocks and transformed into a capable AMC.

All four were required by the Portuguese port authority to give up their ship's radios and a few antiquated weapons. They carried a range of cargo, including electric batteries, electric wiring, a large car destined for an Indian prince, mining explosives, drums of kerosene and many other articles, which were left undisturbed by the Portuguese.

There was also a problem with the crew of these ships; 211 in total (122 Germans, 50 Italians and 39 Indians) and not surprisingly, these men became increasingly bored and fractious as time went by. All their activities were closely watched by the British Consul, who was extremely suspicious, sending regular reports to the government in New Delhi and periodically making informal – sometimes even formal – complaints to the governor-general Colonel Cabral.

Special Operations Executive (INDIA) (SOE(India))

The SOE's India Mission was established in May 1941, its aim being to conduct clandestine tasks outside the scope of other overt or covert organisations. One of its earliest operations was the kidnapping of a German intelligence officer named Robert Koch and his wife from Portuguese Goa to British India. The Dutch East Indies Intelligence service warned their British counterparts in 1939 that this man was an officer in the Abwehr, the German military intelligence organisation, but when Ehrenfels took refuge in Mormugão Koch rented a bungalow ashore but was unable to leave the Portuguese colony, so that he and his wife appeared fated to remain in Goa until the end of the war.

The British consul in Goa repeatedly informed New Delhi of the threat Koch posed, and in November 1942 Major Stewart of SOE(India) carried out a reconnaissance which led to Operation Hotspur in December 1942. False documents were prepared, following which Stewart and another officer named Pugh acquired a Ford station wagon in Bombay, had it repainted and fitted with false number plates and hid some incendiary devices which they planned to use to burn down Koch's bungalow. Their false documents enabled them to pass through Portuguese customs without any problem and on arrival in Panjim they had lunch with the British consul, but what happened the next day has never been resolved. It is certain that the two British officers crossed the frontier into British India, accompanied by Robert and Mrs Koch. One version of these events claims that Mrs Koch was sick and her husband willingly took her into British India for treatment in a British hospital. The other version is that they were forcibly kidnapped and then drugged, before being taken across the frontier. What is certain is that they disappeared in British India and there is no trace as to what happened to them.

The Plans

Both the British and the Axis captains had their plans. In late October 1942 an SOE(India) conference was told that a radio broadcast was being made every night from a ship in the harbour it was claimed that she a proliferation of antennas indicating that she carried more than the normal merchant ship radio installation. All agreed that action was required but that nothing must be done which might infringe Portuguese sovereignty. It was also decided that attempts should be made to bribe the Master of the Ehrenfels, Captain Röfer, and carefully selected members of his crew. In a signal London told SOE India that: “…the Foreign Office will raise no objection if this operation is carried out without violence or overt action within Portuguese territorial waters, and provided that the words “trickery" and “chicanery" in your letter mean “Bribery" pure and simple, and nothing else."

British commanders were adamant that they would dearly like to see the four Axis merchant ships incapacitated, but were not prepared to assist in any way, although the Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Army agreed that elements of the Calcutta Light Horse and Calcutta Scottish might take part in a special operation. From this point on planning went ahead without interruption, SOE India being certain that there was serious deterioration in morale aboard Ehrenfels and a large part of the crew would be willing to cooperate with Allies.

The SOE plan was based on four elements. First, to bribe as many as possible of those in responsible positions aboard Ehrenfels. Secondly, to further reduce the effectiveness of the crew by luring as many as possible ashore, following which the ship would be seized and steamed outside the three-mile limit. But, however much they hoped for a peaceful outcome it was deemed prudent to include an armed party to deal with unexpected contingencies.

In January SOE(India) continued to make contact through cut-outs with some members of Ehrenfels' crew, including the captain, with substantial sums of money being offered as bribes. Unfortunately, the British agents also learnt that there were at least two dedicated Nazis aboard who should not be approached: the chief officer, and the head steward.

Preparations were going ahead in India, but in early February they hit another snag, “ SOE London responded on 6 February that it would be impossible to obtain any help from London but then signalled that no further help was needed “…as we have made satisfactory local arrangements."

The German Plan

The British had a plan, but so, too, did the Axis captains, who were well aware that their ships must be a target for a raid by British forces. Their main counter was a plan to scuttle their ships, and observers on the shore saw their crews conduct regular drills in which they practised opening the seacocks at very short notice They also placed explosives and combustible materials in the holds, engine rooms and intermediate decks. A system of alarms using repeated blasts on their ships' sirens was also agreed. It is often said that military plans are good until the first shot is fired and that was certainly the case here, as will now be seen.

The Units and the Men

The SOE had a plan and needed the men to accomplish it and, in the event, almost all the manpower needed for Operation Longshanks was found in Calcutta auxiliary units. Most came from the Calcutta Light Horse (CLH), raised in 1872. Their purported role was defence of their area in the event of a foreign invasion, but it was clearly understood that their real mission was “aid to the civil power" in quelling communal unrest, especially any recurrence of the never-to-be-forgotten Indian Mutiny. These units were essentially mounted infantry, using their horses for rapid movement, but fighting dismounted. All personnel were Europeans, an unusual feature being that the officers were elected by the men, their commission then being confirmed by the Viceroy, but promotion thereafter followed the usual army practice.

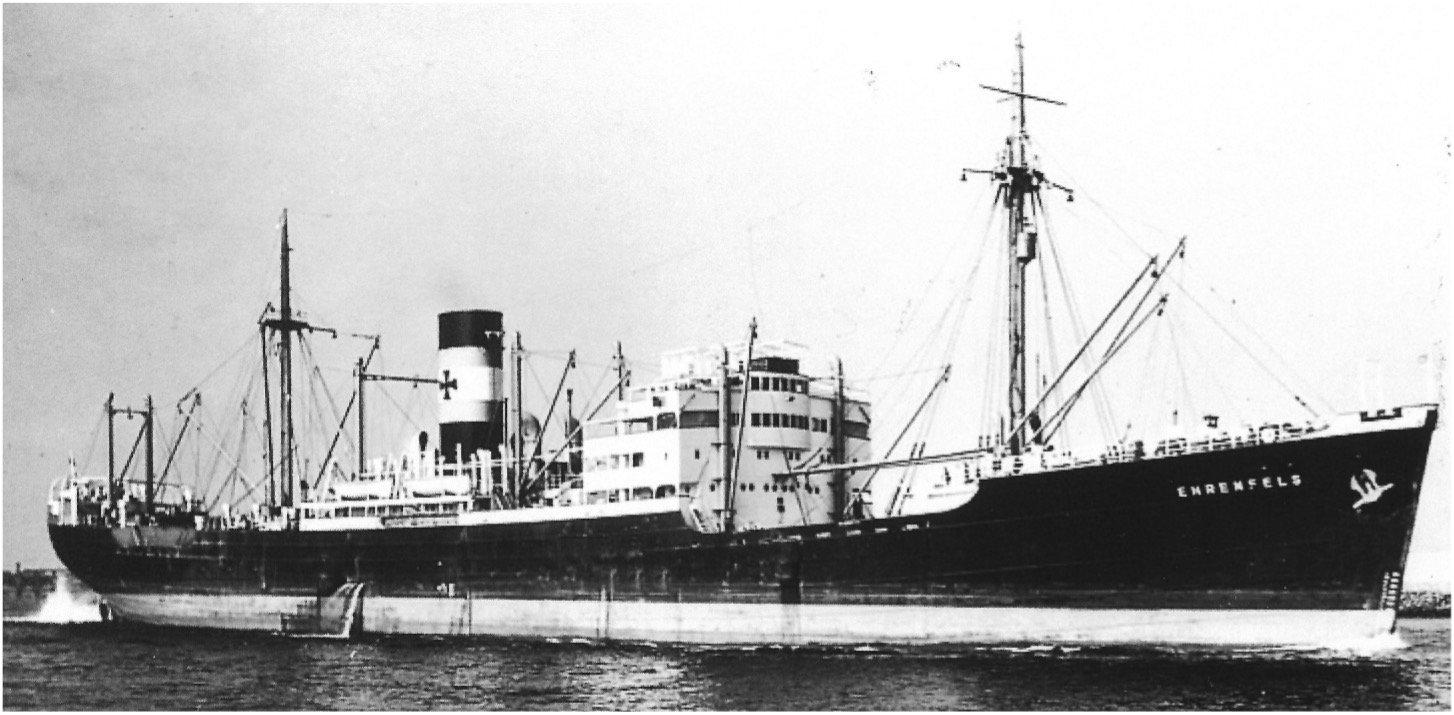

In early 1943 Lieutenant-Colonel Pugh of SOE India Mission approached his friend, Lieutenant-Colonel Grice, Commanding Officer of the CLH, with a request for help. Grice was 45 years old. He joined ICI in India in 1919, and enrolled in the CLH as a trooper in 1920 took command as a lieutenant-colonel in 1939. When he was asked to assemble a party of fourteen men for an undisclosed task at an unknown destination, he set four criteria. First, that the participants should be volunteers; second that they should be fit and suitable for this unspecified mission; third, that they should be unmarried; and fourth that they should, wherever possible, be under 35 years old.

3 - Lieutenant-Colonel Grice, Commanding Officer of the CLH.

Grice himself broke both the unmarried and age rules, but he was the Commanding Officer and was determined to lead from the front. As shown in the table, the other thirteen men selected were, with two exceptions, under 35 years old, and, Sandys-Lumsdaine apart, were unmarried. The average age was 33.6 years. By employment there were: accountants – six; management – six; insurance – one; and banking – one.

Four volunteers from the Calcutta Scottish also took part in the operation. [Table 4] This was an infantry battalion of the Auxiliary Force, whose personnel were recruited mainly from the many Scots in the East Bengal jute industry. As the Calcutta Light Horse had more than sufficient volunteers it is assumed that the Calcutta Scottish brought some special skill to the operation, which could have been weapon handling where, as infantrymen, their skills could have been greater than those of the CLH, or it might have been handling explosives, in which they had received recent training.

Thus, the attack force for the operation comprised twenty-four men: six from SOE, four from the Calcutta Scottish and fourteen from the Calcutta Light Horse. There was one professional soldier, one had been a professional, four were wartime soldiers, the remainder were part-timers from the two Calcutta volunteer units. The oldest was 45 and the youngest just 25.

In Calcutta the men started intensive training on 19 February, which actually amounted to no more an hour before breakfast, although it was conducted by regular sergeants and covered revolvers, Sten guns and unarmed combat. They were also given a list of personal kit they were to take with them. This included military field uniform; steel helmet; bedding roll; knife, fork, spoon, plate, mug; washing items; and first field dressing. Every man also had to carry a Service revolver and eighteen rounds of ammunition. They were assembled again on 26 February to be given their orders for the move. They were told that they were to travel by train in civilian clothes and would be divided into small groups, each keeping separate from the others. They were to report to the station at Calcutta, where they would be given their tickets to Madras, and once there they would be given further tickets for the onward journey to Cochin. The first group of two CLH men left that day, followed by five men in two groups on Saturday 27th and the remaining seven on Sunday 28th. The CS travelled in one group. After endless games of cards, numerous cigarettes and a few nips from the single bottle each man was allowed to carry the twenty-four reached Cochin safely and on schedule, where they met the SOE officers who had travelled to Cochin by a different route.

The Voyage of Hopper Barge Number 5

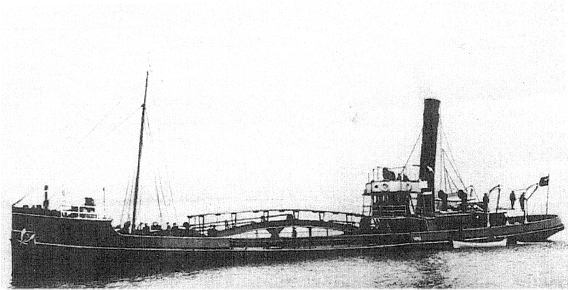

The SOE planners had concluded early in their deliberations that that the only realistic method of approaching the Axis ships was from the sea, but the ship which made the operation possible was singularly undistinguished. Hopper Barge Number Five (affectionately known as Phoebe) was thirty years old and owned by the Port Commissioners in Calcutta. Its sole task was to keep navigable channels clear by collecting silt removed from the bottom by a dredger and taking it out to sea where it was dumped. These were essentially daylight-only, fair-weather vessels with a small forecastle, large open-topped hopper taking up the entire midships section, and a section aft containing the engine, propeller, steering and bridge. Other amenities such as accommodation, cooking and toilets were minimal. Phoebe also had a raised gangway running lengthways above the hopper, linking the forecastle and superstructure aft.

Hopper Barge Number Five (Phoebe).

Phoebe was built in Glasgow, Scotland and launched in 1912. It had a design displacement of 1,200 tons, with a length of 61m, an 11.6m beam and draught of 4.9m. Phoebe was powered by two coal-fired steam engines driving two three-bladed propellers, which gave a maximum speed of 11 knots, although thirty years later this was probably no more than 8-9 knots at best, with a speed of advance of approximately 6-7 knots. Although built specifically for coastal and estuarine work, it is to her credit that in 1913 it safely made the 8,000 nautical miles delivery voyage from the Clyde to the Hooghli.

Phoebe had a crew of three officers and twenty-five sailors, who were well used to the daily round of loading and dumping silt in the Hooghli estuary. On this occasion, however, they were told that the vessel was going to take part in a military training exercise, which would involve several days absence, although great care was taken not to mention their actual destination, nor the possibility of actual action.

In command of Phoebe for this voyage was Commander (retired) Bernard Davies (44), a former Royal Navy officer, who was employed by the Port Commissioners of Calcutta as an Assistant Conservator and thus well acquainted with Phoebe. Davies had no hesitation in volunteering for Operation Creek.

Phoebe's capacious hopper was used to carry a large amount of coal, sufficient for the entire voyage to Bombay, as well as water and rations for the crew and passengers. She also carried military stores, including machineguns, rifles, ammunition, explosives and items needed for the attack such as bamboos, timber, railway sleepers, rope, grappling irons and bags of cement. Her peacetime role did not require Phoebe to carry any radio sets, but two were installed for this operation.

Phoebe's route was from Calcutta to Trincomalee where she spent a night, then south-about around Ceylon to Cochin, where she picked up all the passengers and thence to Goa for the operation. That concluded, she sailed to Bombay, disembarked the passengers and then returned to Calcutta. Assuming a speed of advance of 6 knots, the voyage can be reconstructed as follows. The voyage from Calcutta to Trincomalee and thence to Cochin went well, arriving on the morning of 5 March, anchoring a short distance offshore. First aboard was the SOE party, followed by the Calcutta Light Horse in the early afternoon and finally the Calcutta Scottish. As soon as all twenty-four were accounted for Davies weighed anchor and once the ship was clear of the harbour turned her southwards until out of sight of land, when he reversed course and headed north. The men from Calcutta were briefed and were told that their destination was Mormugao Harbour where three German merchant ships were lying at anchor, but that this operation was intended to 'acquire' only Ehrenfels. They were also told that British agents would encourage some locals to organise parties which would be attended by at least some of the Axis ships' crews. Agents would also try to bribe the captain and other members of his crew to cooperate in taking Ehrenfels out to sea, where a Royal Navy ship would take over and tow Ehrenfels to Bombay. The briefers explained that the reason for using members of the CLH, the CS and a civilian ship and crew was so that, if captured, they could be disowned by the British as over-enthusiastic amateurs who had taken it upon themselves to undertake this raid. The meeting closed with them being issued with 30 Rupees each and told that if anything went wrong, they were to get ashore and make their way to the Burmah-Shell Refinery, whose manager had been warned of the possibility of 'visitors'.

The men trained throughout the voyage and were given the exact routes to follow. Rehearsals were carried out; a password was issued and finally everyone had to sew a white cotton disc on the back of their shirts. The morning of the 8th was devoted to preparing for action, with bamboo ladders and other stores placed ready, while a protected emplacement was constructed on the bridge wing for the Bren gun. The firefighting appliances were made ready and all unwanted gear stowed where it would not interfere with the activities on deck. At 2100 everyone blackened their faces and hands, donned helmets, checked weapons, and then rested. The weather was calm, calm with good visibility (it was a New Moon) and high tide was at 0036.

At 0100 9th March everyone took up their positions. On the forecastle were the assault groups with ladder and grappling irons ready, and a man whose task was to answer challenges in either Portuguese or German. Amidships were the carrying parties ready to launch their ladders and carry any stores requested, plus the firefighting party with their extinguishers. At 0145 Phoebe approached the buoy marking the entrance to the harbour and Davies ordered members of the ship's crew to suspend ropes and fenders over the starboard side.

At about 0215 Phoebe passed unchallenged under stern of Braunfels and set course for Ehrenfels. When they were very close to their target the men on the forecastle heard shouts of “Achtung! Achtung!" from Ehrenfels which was now towering over them, followed by a challenge in English. A searchlight was aimed at Phoebe, but Stewart shouted, somewhat dramatically, “Let them have it," and a burst of automatic fire shot out the lights and forced the German afterguard to flee. Despite this distraction, Phoebe was placed with great skill alongside Ehrenfels, abreast the after well-deck and the grappling irons successfully thrown. There was a momentary hiatus as Phoebe still carried some way and the ladder tangled with the mainmast shrouds, but a touch of 'astern' brought her back to the correct position. As soon as the ladder was freed, by which time it was about 0225, two men held the ladder while the designated men quickly swarmed up it and dispersed to their allotted tasks. At this point, according to the official report, the British came under fire from Ehrenfels' crew members.

Meanwhile, Captain Röfer had reached the bridge and started to sound the agreed signal on the ship's siren to alert the other Axis ships. He had no sooner started than the first of the SOE party burst into the bridge, and when Röfer refused to stop, he was immediately shot and killed. There is no mention in any of the accounts of the CLS or CS firing any shots at this point, so it appears probable that this must have been done by one of the SOE parties. Corporal Turcan and his CLS group followed the SOE up the boarding ladder and after a brief pause to hold it steady for the next group followed the SOE party to the bridge where they saw the captain lying on the floor, already dead. In accordance with the plan, the bridge was cordoned off while the other groups fanned out around the ship to capture any crew and to assess the state of the engines.

Meanwhile, Ehrenfels' Chief Engineer had reached the engineroom, secured the steel doors behind him, blown the scuttling charges, ordered his men to open the seacocks and begun planned sabotage on the engines. When the raiders reached the engineroom, Captain White, the SOE explosives man, used a magnetic charge to blow the door off its hinges and then entered but it was immediately obvious that he was too late, although the actual extent could not be ascertained in the time available. The Chief Engineer also initiated the incendiary charges, starting intense fires which eventually engulfed the whole ship, following which he jumped into the sea and swam ashore. All concerned, including his enemies, acknowledge that he was a brave man who did his duty with great efficiency. Three men searched the crew's quarters but only found one person, a cabin boy, whom they took prisoner and when they subsequently heard the recall signal took him with them back to Phoebe.

Meanwhile, another two men headed for the Chief Engineer's cabin, their orders being to ask him if he was prepared to power up the ship to take it to sea and if he refused, they were to shoot him on the spot. On the way to the cabin, they bumped into a steward and manacled him to the ship's rail. The two men then tried to enter the cabin but found that the Engineer had already left and the cabin was ablaze. Duguid dashed off to get an extinguisher, which Crossley used until he could stand the heat no longer, when he staggered out and asked Duguid to finish off the job.

Also, at this stage the fifteen MiniMax fire extinguishers were carried aboard Ehrenfels and stacked on the after well-deck for use if the Germans set fire to the ship, but, when the fire did break out, it was so fierce that they were of no use and had to be abandoned. By 0235 hours Ehrenfels had sunk some 12 feet and was sitting on the bottom and this, coupled with the ferocious fire, made it clear that there was no question of taking her out of the harbour, let alone reaching Bombay. So, repeated blasts were sounded on Phoebe's siren and the British men returned at once, bringing with them three prisoners. Evacuation was completed by 0240 and as soon as all men were accounted for Phoebe cast off and at 0315 passed the outer buoy and set course for Bombay, transmitted a success signal over both radio links.

The British suffered no losses, although three of the SOE officers were slightly wounded. SOE estimated that sixteen Germans had been killed, including the captain and the majority of ship's officers, but the Portuguese authorities found only five bodies, all of them burned beyond recognition, although one was identified as that of Captain Röfer.

To those on the shore the first sign that anything was amiss was a series of double hoots on ships' sirens at about 0100, and within minutes Braunfels was seen to be on fire, followed quickly by Drachenfels and some minutes after that by Ehrenfels. Crewmen from the German ships were soon reaching the shore - in ships boats, canoes, and, in several cases, by swimming. Anfora was seen to start its fires about an hour after the Germans and soon its crew also arrived at the shore, to taunts from the Germans that “Italy is late as usual.".

The Portuguese police were quickly on the scene, followed by a platoon of African troops, the latter proceeding to round up every non-Portuguese European at the point of the bayonet, including, for a short time, the British consul. Neither the German nor Italian crews offered any resistance and all 106 surviving Axis personnel were taken to Nova Goa. Daylight revealed four burning, grounded ships. It was quickly established that all men from Anfora, Braunfels and Drachenfels could be accounted for, but there were five bodies, one of which was identified as that of Captain Röfer but three could not be found at all.

The Portuguese arrested all those who had been aboard the ships at the time of the attack and charged them with setting fire to and scuttling their ships. Those who had been ashore at parties at the time could obviously not be faced with similar charges, and were simply interned. The hulks and what remained of their cargoes were sequestrated and became Portuguese property.

The Germans crews were unanimous in stating that all three ships had been boarded by armed and masked men from small boats carrying eight men each. They were quite convinced that these had all come from a British tanker, which happened to be in port at the time delivering fuel to the colony. On the other hand, the captain of the Anfora said that he had seen a small steamer draw up alongside, first, Ehrenfels and, subsequently, Braunfels and Drachenfels and then put to sea again. The much-derided Italian captain was very nearly correct, but his credibility was challenged when it was pointed out to him that the fires aboard his own ship had been started at least one hour after he alleged that the “small steamer" had put to sea again.

On 17 March the Governor-General discussed the affair with Bremner and said that he knew that the ships' captains had made preparations to fire and scuttle their ships in an emergency, but that nobody could explain just what emergency had arisen to cause the plan to be implemented on the night of 8th/9th. He was also aware that there had been unrest aboard Ehrenfels, whose captain was considered harsh towards his crew, while the chief officer was well-known to be a convinced Nazi. This led the Governor-General to conclude that there must have been an armed uprising aboard Ehrenfels, which explained the shots that had been heard, the death of the captain and the cartridge cases that had been found the following morning, although the discovery of a number of unused fire extinguishers remained puzzling. Bremner was, of course, more than happy to agree with the governor's analysis of what had happened.

Since Portugal was not at war with either Germany or Italy, the former crews of the Axis ships became internees. Those that had been aboard ship at the time of the scuttling were all arrested and held in a fortress, while those had been ashore were given licence to a degree of freedom within Goa. All were a distinct nuisance to the Portuguese authorities in that they had to be housed, fed and provided with medical treatment, while, although their expenses were in theory the responsibility of their parent countries, British controls meant that it was very difficult for the German government to get money through, while Italy was effectively bankrupt, anyway.

In early 1944 the Portuguese Government proposed that six sick German seamen should be repatriated in exchange for a like number of British merchant seamen held in Germany. Then, since Italy had signed an armistice in September 1943, in April 1944 the British Ministry of Economic Warfare proposed that all the Italian seamen should be repatriated. These proposals were then discussed in a very desultory manner between various departments in London, the British Indian government in New Delhi, and the embassy in Portugal. It is clear from the correspondence that while no department had any serious objections, none of them was particularly enthusiastic, either, and in January 1945 the proposal simply petered out. With the end of the war, the majority of these internees were quietly sent home, although several are believed to have settled in Goa.

The three men missing from Goa were, in fact, in British hands. Although ordered not to do so, when the British raiders abandoned Ehrenfels they took with them three German prisoners, who were employed as gardeners and labourers by SOE and seem to have been content with their lot. At the war's end they refused to return to Germany and wanted to become British citizens and, of course, they knew a great deal about the raid on Ehrenfels and its participants, which was intended to remain a state secret for at least another thirty years. After some bureaucratic squabbling Heinz Wilhelm Bernadini changed his name to Peter Shortland and was naturalized in October 1948 and it is assumed that the other two were treated the same.

Assessment

The Axis merchant ships in Goa presented a long-running problem for the British. The major threat was that Ehrenfels would escape and be converted to an armed merchant cruiser, but later, when the Allied shipping losses in the Indian Ocean in 1942 became serious, it was inevitable that operational and intelligence staffs should cast around for possible explanations. Operation Longshanks had three main aims, the first of which was to remove Ehrenfels from Goa. If this was achieved it would silence the alleged radio station aboard the ship and thus, it was hoped, reduce the effectiveness of German U-boats operating in the Indian Ocean. Also, this would neutralise the maritime threat posed by the Ehrenfels should it escape and be outfitted as an armed merchant cruiser. It is important to note, however, that at no stage was Longshanks concerned, in any way, with the other three Axis ships.

The numerous U-boat successes against Allied merchant ships in the Indian Ocean in 1942 and early 1943 were a matter of grave concern to Allied planners. One possibility, based on proven examples of U-boats entering Spanish ports to replenish from Axis merchant ships, was that the four ships in Goa might be supplying U-boats with fuel and other supplies. However, this author's detailed examination of all U-boat records for the Indian Ocean shows no evidence whatsoever of such visits to any Indian port.

The second Allied suspicion was that information on sailings from Bombay was being collated by a spy and then taken by courier to Goa from where it was transmitted to waiting U-boats by a wireless hidden aboard the Ehrenfels. There was a known Portuguese government radio station in Goa, but this had been the subject of intense diplomatic pressure from the British earlier in the war and by mutual agreement was not being used for anything other than Portuguese government traffic. Again, nowhere is there the slightest indication that U-boats were receiving information from clandestine transmitters anywhere on the Indian sub-continent, let alone Goa.

There is a perception that the men from these two units were middle-aged amateurs who had somehow got themselves involved in a real-life drama, but these men had all served in their units for some years, which had included basic military training. The ship Phoebe has also come in for adverse comment, due mainly to its age and appearance. However, the fact is that it did all that was required of it, sailing a considerable distance, keeping to the schedule required in the operation order, delivering the raiders to precisely the spot required, and then taking them on to Bombay. The Bengali crew are barely mentioned anywhere. Approximately twenty strong, they were misled into believing that they were going on a short-range military exercise but by the time they reached Trincomalee they must have realised that not all was what it seemed. More than that, not one word seems to have leaked out after their return – no rumours were reported from the Calcutta waterfront, no startling revelations in the local newspapers.

The Germans contributed significantly to the Allied success, as their arrangements for destroying their ships worked so well. The fires were started as soon as the warning siren sounded and spread so rapidly that there was no chance of extinguished them. Scuttling was also achieved quickly and was no chance of stopping it.

The situation ashore was confused by conflicting reports by eyewitnesses. Some stated that masked raiders had arrived in rowing boats from a British tanker which happened to be in port at the time of the raid and that they had boarded all three German ships. Others claimed that there had been a mutiny aboard the Ehrenfels, where many of the crew were known to be very discontented, and that Röfer (and perhaps others) had been killed by their own crew.

In summary, Operation Longshanks had achieved the total elimination of the threat of any of the four ships escaping from Goa, which came as a great relief to the RN and RIN. All surviving Axis crew members had been rounded up by the Portuguese and either imprisoned or interned. There had been no losses among members of the raiding party nor among Phoebe's crew, all of whom returned home safely. Finally, British involvement was never publicly suggested and if some of the Portuguese officials had any suspicions, they kept them to themselves.

There was an unusual postscript which showed that the neutral status of Goa had not been compromised. Just six months after Operation Longshanks there was a large-scale exchange of civilian internees between the United States and Japan, which was organised and supervised by the International Committee of the Red Cross, and hosted by the Portuguese authorities in Goa. The Swedish liner, Gripsholm, under charter to the US government, and the Japanese Tiea Maru sailed under 'safe passage.' A total of 1,513 Japanese were exchanged for 1,503 Americans. Teia Maru arrived on 15th followed by Gripsholm on 16th October and the exchanges took place on 19th. The ships sailed from Mormugao on 21st and 22nd and returned unmolested to their original ports.

Table 1. The Four AXIS Merchant Ships[1] *None were aboard on 8/9 March 1943

|

MV EHRENFELS |

SS DRACHENFELS |

MV BRAUNFELS |

SS ANFORA |

|---|

Flag |

Germany |

Germany |

Germany |

Italy |

Owner |

DDG-Hansa |

DDG-Hansa

|

DDG-Hansa

|

Lloyd Triestino |

Builder |

DeSchiMag |

Howaldtswerke |

DeSchiMag

|

San Rocco |

Entered Service |

1936 |

1921 |

1927 |

1922 |

Length |

154m |

134m |

149m |

123m |

Beam |

18.7m |

17.2m |

18.4m |

16.5m |

Draught (full load) |

8.27m |

9.26m |

8.3m |

7.7m |

Displacement |

7,752grt |

6,342grt |

7,847grt |

5,452grt |

Deadweight |

10,250 tons |

9,250 tons

|

11,200 tons |

8,504 tons |

Propulsion |

Diesel |

Steam |

Diesel |

Steam

|

Cruisin (full load) |

16 knots |

12 knots |

12 knots |

10 knots |

Crew |

44 |

33 European

39 Indian |

45 |

50 |

Passenger Capacity* |

12 |

4 |

7 |

10 |

Arrived Goa

|

28 Aug 39 |

28 Aug 39 |

1 Sep 39 |

10 Jul 40 |

Table 2. Participants from Calcutta Light Horse. Notes: Ages and ranks shown are as on the date of the operation. *Denotes those with civil occupation of accountant

NAME

| RANK | AGE

| CIVIL EMPLOYMENT

|

|---|

|

BRYDEN, William Donald |

Trooper |

29 |

Bengal Chamber of Commerce |

CLARKE, Geoffrey Hayman John |

Trooper |

35 |

Imperial Tobacco Co of India |

FARMER, Frank Darrell |

Corporal |

35 |

James Finlay & Co Ltd* |

FERGIE, Kenneth Rishton |

Lance-Corporal |

32 |

George Henderson & Co Ltd* |

GRICE, William Henry |

Lieutenant-Colonel |

45 |

I.C.I. (India) Ltd |

LAW, Colin James Drummond |

Lance-Corporal |

37 |

Hongkong & Shanghai Bank |

MACFARLANE, Alistair Forbes |

Lance-Corporal |

40 |

Jardine Skinner & Co |

NOBLE, William Mathewson |

Lance-Corporal |

33 |

Commercial Union Assurance |

SANDYS-LUMSDAINE, Colin Cren |

Lieutenant |

35 |

Williamson Magor & Co |

STENHOUSE, Nicol |

Lance-Corporal |

31 |

Andrew Yule & Co Ltd* |

TANNER, John Darley |

Trooper |

27 |

Lovelock & Lewes* |

TURCAN, Charles Ian |

Lance-Corporal |

28 |

Andrew Yule & Co Ltd* |

WATSON, Cecil Herbert |

Lance-Corporal |

32 |

Shaw Wallace & Co Ltd |

WILSON, Ian Birrell |

Trooper |

32 |

Ford, Rhodes, Thornton & Co* |

Table 3. Participants from Calcutta Scottish

NAME |

CIVIL EMPLOYMENT |

Duguid, Robert Hutton |

Duncan Brothers * |

Miller, William |

India Tyre |

Patterson, James (Jimmy) |

Surveyor, marine engineer |

Wylie, Gilman |

Norwich Union |

Table 4. Phoebe voyage

| DEPART |

ARRIVE |

DISTANCE (NM) |

Calcutta |

19 Feb |

Trincomalee |

27 Feb |

1,091 |

Trincomalee |

28 Feb |

Cochin

|

5 Mar

|

780 |

Cochin |

5 Mar |

Marmugao |

8 Mar

|

333 |

Marmugao |

9 Mar |

Bombay |

10 Mar |

278 |

TOTAL | |

| |

2,482 |

[1] Source: World's Merchant Fleets, 1939, Jordan, RW, Chatham Publishing, London, 1999

David Miller

Após 36 anos no Exército Britânico, David Miller, deixou a carreira militar, dedicando-se ao jornalismo e à escrita de livros, maioritariamente no âmbito da História Militar. Tendo publicado dezenas de livros, revela-se um autor eclético tendo escrito obras que vão desde Ricardo Coração de Leão, passando pelos samurais até à Guerra Fria. Reside actualmente na Austrália.

Descarregar este texto

Descarregar este texto

Como citar este texto:

MILLER, David – Operation Longshanks. Revista Portuguesa de História Militar - Dossier: Portugal no Contexto da Segunda Guerra Mundial, 1939-1945. [Em linha] Ano III, nº 4 (2023). [Consultado em ...], https://doi.org/10.56092/XUVD8950